Inez Milholland, New York City attorney and suffrage leader, was one of the most visible and respected advocates for women's equality in the early 20th century. Her death in Los Angeles of pernicious anemia on November 25, 1916 shocked and saddened her colleagues, who believed her leadership and sacrifice to win Votes for Women made her a martyr to the cause.

To recognize Inez on the centennial of her death in 2016, California Representative Jackie Speier, working with the Centennial project, nominated her for the Presidential Citizens Medal, the second highest civilian award of the nation. As it turned out, no medals were awarded that year.

The biographical summary and nomination below offer an overview of Inez's contributions. They are followed by the Eulogy that suffragist Maud Younger delivered at the Washington D.C. Memorial for Inez in 1916. They all offer a sense of Inez and her place in American history.

_____________________________________________________________

Read the account at the bottom of the page or listen to the Memorial for Inez in Washington D.C. on Christmas Day 1916. Audio selection from Librivox, Inez Milholland tribute, 1916. From Jailed for Freedom by Doris Stevens, 1920.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

2016 Nomination for the Presidential Citizens Medal

INEZ MILHOLLAND BOISSEVAIN

Attorney and American Suffrage Martyr

August 6, 1886 – November 25, 1916

During her brief life, New York attorney Inez Milholland Boissevain became one of the most widely recognized advocates of Votes for Women in the United States. Today, as the nation approaches the centennial of American women voting in 2020, Inez symbolizes the perseverance and sacrifices that were required to win equality for women as full American citizens. With courage, conviction, and dedication, this fallen young leader exemplified public service to the nation and an unwavering dedication to basic civil rights as the cornerstone of democracy.

At a time when women had virtually no political power and no representation in government, Inez Milholland championed their civil rights, particularly the right to vote, and made substantial contributions to winning the political liberty women enjoy today. She firmly believed that winning enfranchisement would offer women a voice and a place in government, thus strengthening the nation as a whole.

Born in Brooklyn and raised in New York and London, Inez became an advocate for the rights of women while a student. When the president of Vassar College banned her woman suffrage meeting on campus, Inez led the assembled students and guests to a meeting in the cemetery across the road.

Between 1910 and 1916, she became a central figure involved in planning, speaking, and raising funds for the drive for Votes for Women in New York State. She chaired meetings, answered opponents’ arguments, lobbied state legislators, and led suffrage parades up Fifth Avenue. Robed as the “free woman of the future,” she became nationally known for her role as a mounted herald leading the great March 3, 1913 suffrage procession in Washington, D.C. that involved thousands of supporters and political figures. Four months later, she married Dutch businessman Eugen Boissevain.

Attracted to law school by a desire to protect women and children, Inez faced rejection by Oxford, Columbia, and Harvard because she was a woman. New York University finally accepted her. Even before earning a law degree in 1912, she advised and supported working women and shirtwaist strikers who had no direct political representation or money for lawyers. She believed that “the way to right the wrongs of civilization and to strike a blow at poverty was by means of concerted and intelligent political action and the making of sound laws.”

One of few women attorneys in New York, Inez specialized in criminal and divorce cases but faced prejudice and other obstacles to securing paying clients. She vigorously participated in a grand jury investigation into conditions at Sing Sing Prison and once raced to win a last minute reprieve for a laborer sentenced to die. Having seen the brutal conditions in prison, she spoke out for reform, opposed capital punishment, and assisted individual inmates with filing appeals and finding jobs.

Like her father, John Milholland, the first treasurer of the interracial NAACP, Inez opposed racial discrimination, supported the rights of workers, and advocated a wide range of reforms including international peace. At the beginning of World War I, she joined Henry Ford’s “Peace Ship,” which unsuccessfully tried to steer the European warring parties into mediation.

Woman suffrage, however, is the cause to which she is most closely linked, and the cause to which she gave her final effort. Expanding on her years of experience as a leader in New York City, Inez became a “Flying Envoy” for the National Woman’s Party on an October 1916 election year speaking tour of the west. In city after city in seven western states, she spoke with passion and conviction to women who were new voters: “Now, for the first time in our history, women have the power to enforce their demands and the weapon with which to fight for woman’s liberation.” Barnstorming for the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, she declared, “Liberty must be fought for. And, women of the nation, this is the time to fight.”

When her health failed during the strenuous tour, Inez put off medical treatment rather than quit. In late October, exhausted and overcome by pain, the young suffragist collapsed while demanding liberty on a stage in Los Angeles. A month later, despite repeated blood transfusions, she died of pernicious anemia, having just turned 30. Fellow suffragists recognized that her leadership, love of democracy, and devotion to women made her a martyr to the cause.

Inez was buried in Essex County, New York, and on Christmas Day 1916 the Woman’s Party held an unprecedented memorial for her under the rotunda in Statuary Hall in the national Capitol. She became the first woman to be so honored. A week later, aroused by her sacrifice, suffragists began to picket the White House demanding that President Woodrow Wilson support for the suffrage amendment. Throughout the year, their banners carried her final plea: “Mr. President, How Long Must Women Wait for Liberty?” Inez inspired thousands of suffragists through the final, climactic years of the movement and her memory lived on in the ensuing years.

Inez Milholland Boissevain spent her life seeking justice, equality, and civil rights for American women. Because of her work, and the persistence of tens of thousands of American suffragists from 1848 to 1920, the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ensures women’s voting rights now and for future generations.

__________________________________

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This is the full text of the letter Representative Jackie Speier sent to President Obama formally nominating Inez Milholland for the Presidential Citizens Medal.

November 4, 2015

The Honorable Barack Obama

President of the United States of America

The White House

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20500

Dear Mr. President:

I have the great honor to offer the name of Inez Milholland as a nominee for the Presidential Citizens Medal.

Inez Milholland was an attorney as well as an advocate for workers' rights, prison reform, race and class equity. But she is best remembered as a shining star in the pantheon of inspiring leaders of the women's suffrage movement in the early 20th century.

As a college student, she was introduced to the suffrage movement by Emmeline Pankhurst and began her suffrage crusade as the leader of the unsanctioned Vassar Votes for Women Club. Shortly after her Vassar graduation, she came to public attention when she shouted from a window with a megaphone urging the vote for women – nearly stopping the passing Republican election campaign parade.

In many ways, Inez Milholland was the public face of the women's suffrage movement - giving speeches at rallies, lobbying legislators and leading parades. She is perhaps best known for her role in the 1913 women's suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., held the day prior to the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson. The parade of some 8000 marching down Pennsylvania Avenue displayed nine bands, 4 motorized brigades, about 24 floats and several mounted heralds. And near the head of the parade, astride a large white horse, rode 26-year-old Inez Milholland – wearing a tiara and flowing white robes.

Inez Milholland continued working tirelessly for the women's suffrage movement for several more years when she embarked – against medical advice because of a medical condition – on a grueling five week, eleven state tour of the western United States. At one of the stops, in Los Angeles, while speaking at a rally advocating for a constitutional amendment for universal suffrage, she suddenly collapsed. Her last public words were "Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?" She never recovered and died in hospital some weeks later at age 30 in 1916. Suffragists at that time termed her a "martyr" for women's suffrage. She was given a martyr's remembrance on Christmas Day, attended by over a thousand people, at a ceremony under the rotunda at Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol – the first woman to be honored in this way.

The aftermath of her death spurred an escalation in the activities of suffragists - they started silently picketing the White House with signs designed to put pressure on the President. One of the most popular picket signs echoed Milholland's last public words: "Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?"

Inez Milholland's leadership in the women's suffrage movement was vital and the circumstances of her last speaking tour and death inspired the intensification of the efforts of women to achieve the vote. The ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 was, in no small way, part of a rich legacy in which Inez Milholland was an integral part.

As the centennial of her death and of the 19th Amendment approach, I can think of no better way to honor her memory than with this long overdue award. Therefore, I am proud to submit the name of Inez Milholland as a nominee for the Presidential Citizen's Medal

Respectfully yours,

Jackie Speier

Member of Congress

14th District, California

_____________________________

November 4, 2015

The Honorable Barack Obama

President of the United States of America

The White House

1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20500

Dear Mr. President:

I have the great honor to offer the name of Inez Milholland as a nominee for the Presidential Citizens Medal.

Inez Milholland was an attorney as well as an advocate for workers' rights, prison reform, race and class equity. But she is best remembered as a shining star in the pantheon of inspiring leaders of the women's suffrage movement in the early 20th century.

As a college student, she was introduced to the suffrage movement by Emmeline Pankhurst and began her suffrage crusade as the leader of the unsanctioned Vassar Votes for Women Club. Shortly after her Vassar graduation, she came to public attention when she shouted from a window with a megaphone urging the vote for women – nearly stopping the passing Republican election campaign parade.

In many ways, Inez Milholland was the public face of the women's suffrage movement - giving speeches at rallies, lobbying legislators and leading parades. She is perhaps best known for her role in the 1913 women's suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., held the day prior to the inauguration of Woodrow Wilson. The parade of some 8000 marching down Pennsylvania Avenue displayed nine bands, 4 motorized brigades, about 24 floats and several mounted heralds. And near the head of the parade, astride a large white horse, rode 26-year-old Inez Milholland – wearing a tiara and flowing white robes.

Inez Milholland continued working tirelessly for the women's suffrage movement for several more years when she embarked – against medical advice because of a medical condition – on a grueling five week, eleven state tour of the western United States. At one of the stops, in Los Angeles, while speaking at a rally advocating for a constitutional amendment for universal suffrage, she suddenly collapsed. Her last public words were "Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?" She never recovered and died in hospital some weeks later at age 30 in 1916. Suffragists at that time termed her a "martyr" for women's suffrage. She was given a martyr's remembrance on Christmas Day, attended by over a thousand people, at a ceremony under the rotunda at Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol – the first woman to be honored in this way.

The aftermath of her death spurred an escalation in the activities of suffragists - they started silently picketing the White House with signs designed to put pressure on the President. One of the most popular picket signs echoed Milholland's last public words: "Mr. President, how long must women wait for liberty?"

Inez Milholland's leadership in the women's suffrage movement was vital and the circumstances of her last speaking tour and death inspired the intensification of the efforts of women to achieve the vote. The ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 was, in no small way, part of a rich legacy in which Inez Milholland was an integral part.

As the centennial of her death and of the 19th Amendment approach, I can think of no better way to honor her memory than with this long overdue award. Therefore, I am proud to submit the name of Inez Milholland as a nominee for the Presidential Citizen's Medal

Respectfully yours,

Jackie Speier

Member of Congress

14th District, California

_____________________________

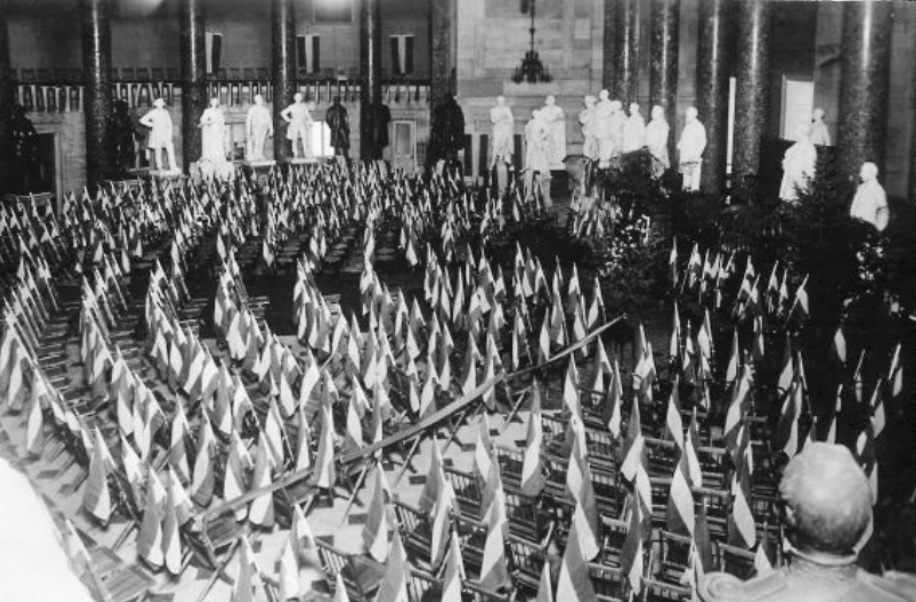

HONORING THE MEMORY OF INEZ MILHOLLAND BOISSEVAIN

Maud Younger, a California suffragist, labor organizer, and national suffrage lobbyist, delivered this Eulogy for Inez at the National Woman’s Party’s Memorial in Statuary Hall in the National Capitol on December 25, 1916. Music and hymns filled the historic venue, which was decorated with evergreen boughs and vibrant purple, white, and gold Woman’s Party flags. Maud Younger's Memorial was reprinted in the Woman's Party's publication The Suffragist, December 30, 1916.

Maud Younger, a California suffragist, labor organizer, and national suffrage lobbyist, delivered this Eulogy for Inez at the National Woman’s Party’s Memorial in Statuary Hall in the National Capitol on December 25, 1916. Music and hymns filled the historic venue, which was decorated with evergreen boughs and vibrant purple, white, and gold Woman’s Party flags. Maud Younger's Memorial was reprinted in the Woman's Party's publication The Suffragist, December 30, 1916.

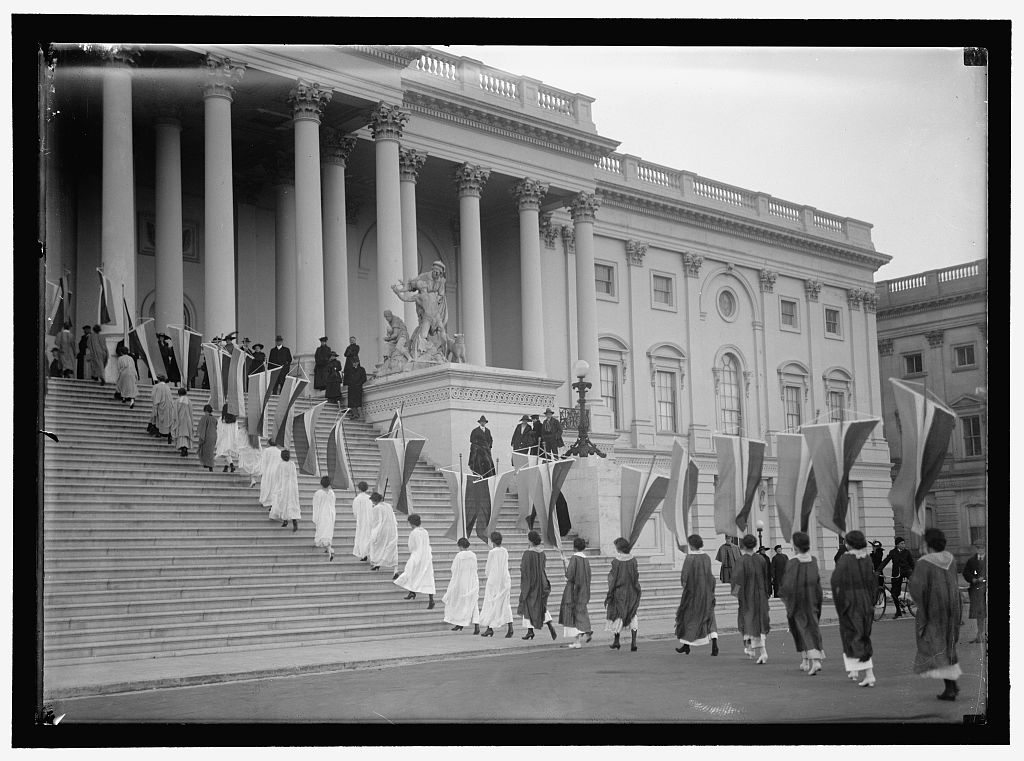

Procession to the Capitol before the Memorial for Inez Milholland Boissevain.

Procession to the Capitol before the Memorial for Inez Milholland Boissevain.

Memorial for Inez Milholland Boissevain

by Maud Younger

WE ARE HERE TO PAY TRIBUTE to Inez Milholland Boissevain, who was our comrade. We are here in the Nation's Capitol, the seat of our democracy, to pay tribute to one who gave up her life to realize that democracy.

We are here that the life she gave should not be given in vain, but that the knowledge of her, the understanding of her, the sacrifice of her, and the inspiration of her should bring to fulfillment the work for which she laid down her life.

Inez Milholland walked down the path of life a radiant being. She went into work with a song in her heart. She went into battle, a laugh on her lips. Obstacles inspired her, discouragement urged her on. She loved work and she loved battle. She loved life and laughter and light, and above all else, she loved liberty. With a loveliness beyond most, a kindliness, a beauty of mind and soul, she typified always the best and noblest in womanhood. She was the flaming torch that went ahead to light the way, the symbol of light and freedom.

She was ever thus in the woman's movement, whether radiant, in white, pinning the fifth star to the suffrage flag when the women of Washington were enfranchised; whether leading the first suffrage parade down Fifth Avenue, valiantly bearing the banner, "Forward into light," or whether in the procession in our Capital four years ago, when, mounted on a white horse, a star on her brow, her long masses of dark hair falling over her blue cape, she typified dawning womanhood.

Symbol of the woman's struggle, it was she who carried to the west the appeal of the unenfranchised, and, carrying it, made her last appeal on earth, her last journey in life.

As she set out upon this her last journey, she seems to have had the clearer vision, the spiritual quality of one who has already set out for another world. With infinite understanding and intense faith in her mission, she was as one inspired. Her meetings were described as "revival meetings," her audiences as "wild with enthusiasm." Thousands acclaimed her, thousands were turned away unable to enter. In this western land she came into her own. Something in her spirit with its intense love of liberty found a kinship in the great sweep of plain and sagebrush desert, in the bare rocky mountains and flaming sunsets. She seemed to breathe in the freedom of the great spaces. Something in her nature was touched by the simplicity and directness of the people. And so on through the west she swept with her ringing message, a radiant vision, a modern crusader.

And she made her message very plain.

She stood for no man, no party. She stood only for Woman. And standing thus, she urged:

"It is women for women now and shall be until the fight is won!

"Together we shall stand shoulder to shoulder for the greatest principle the world has ever known, the right of self-government.

"Whatever the party that has ignored the claims of women, we as women must refuse to uphold it. We must refuse to uphold any party until all women are free.

"We have nothing but our spirit to rely on and the vitality of our faith, but spirit is invincible.

"It is only for a little while. Soon the fight will be over. Victory is in sight."

Though she did not live to see that victory it is sweet to know that she lived to see her faith in woman justified. In one of her last letters she wrote:

"Not only did we reckon accurately on women's loyalty to women but we likewise realized that our appeal touched a certain spiritual, idealistic quality in the western woman voter, a quality which is yearning to find expression in political life. . . . At the idealism of the Woman's Party her whole nature flames into enthusiasm and her response is immediate. She gladly transforms a narrow partisan loyalty into loyalty to a principle, the establishment of which carries with it no personal advantage to its advocates, but merely the satisfaction of achieving one more step toward the emancipation of mankind. . . . We are bound to win. There never has been a fight yet where interest was pitted against principle that principle did not triumph."

Into this struggle she poured her strength, her enthusiasm, her vitality, her life. She would come away from audiences and droop as a flower. The hours between meetings were hours of exhaustion, of suffering. She would ride in the trains gazing from windows listless, almost lifeless, until one spoke; then again the sweet smile, the sudden interest, the quick sympathy. The courage of her was marvelous.

The trip was fraught with hardship. Speaking day and night, she would take a train at two in the morning to arrive at eight. Then a train at midnight and arrive at five in the morning. Yet, she would not change the program; she would not leave out anything. Something seemed to urge her on to reach as many as she could; to carry her message as far as she could while there was yet time.

And so on, ever, through the west she went, through the west that drew her, the west that loved her, until she came to the end of the west. There where the sun goes down in glory in the vast Pacific, her life went out in glory in the shining cause of freedom.

And as she had lived loving liberty, working for liberty, fighting for liberty, so it was that with this word on her lips she fell. "How long must women wait for liberty?" she cried and fell, as surely as any soldier upon the field of honor, as truly as any who ever gave up his life for an ideal.

As in life she had been the symbol of the woman's cause, so in death she is the symbol of its sacrifice – the whole daily sacrifice, the pouring out of life and strength that is the toll of the prolonged women's struggle.

Inez Milholland is one around whom legends will grow up. Generations to come will point out Mount Inez and tell of the beautiful woman who sleeps her last on its slopes.

They will tell of her in the west, tell of the vision of loveliness as she flashed through on her last burning mission, flashed through to her death, a falling star in the western heavens.

But neither legend nor vision is liberty, which was her life. Liberty cannot die. No work for liberty can be lost. It lives on in the hearts of the people, in their hopes, their aspirations, their activities. It becomes part of the life of the nation. As Inez Milholland has given to the world, she lives on forever.

We are here today to pay tribute to Inez Milholland Boissevain, who was our comrade. Let our tribute be not words which pass; nor song which dies, nor flower which fades. Let it be this:

That we finish the task she could not finish;

That with new strength we take up the struggle in which fighting beside us she fell;

That with new faith we here consecrate ourselves to the cause of Woman's Freedom, until that cause is won;

That with new devotion we go forth, inspired by her sacrifice, to the end that that sacrifice be not in vain but that dying she shall bring to pass that which living she could not achieve, full freedom for women, full democracy for the nation. Let this be our tribute imperishable to Inez Milholland Boissevain.

Inez was buried in upstate New York near her family home, Meadowmount, in Essex County, surrounded by the Adirondack mountains.

Listen to an account of Inez's Memorial from Doris Stevens' suffrage classic, "Jailed for Freedom," at https://soundcloud.com/lets-rock-the-cradle/inez-milhollands-story-from.